North Carolina Civil Rights Trail Marker

1964 Sit-ins at Watts Grill

On September 23, 2023, a new NC Civil Rights Trail marker was placed outside of our church.

This is the context and full story behind this inscription.

The Dedication Ceremony was held on September 23, 2023.

To make a donation to help defray the costs of the event, use the Give link and select “Special Gifts” under “Purpose”

January 27, 2024 Luncheon celebrating the 60th anniversary of the sit-ins at Watts Grill.

View Photos of the event

taken by MaryRachel Boyd

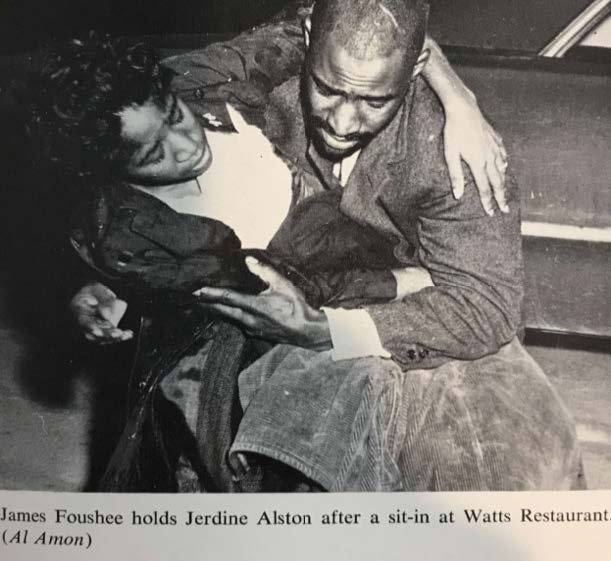

This event was attended by many local civil rights heroes, including David Mason of the Chapel Hill Nine, Women of the Movement Pat Mason, Doretha Foushee, Mary Phillips, Vernelle Jones, Jerdene Alston, Annie B Hargett, Betty Geer, and many others who were involved in civil rights actions during the 1960's. Jerdene Alston and James Foushee were recognized as two of the students who participated in the Watts Grill sit-in on January 5, 1964. Remembrances and further recognitions were made by Danita Mason-Hogans, local historian, and Kenny Mann,Jr., local musician and radio personality.

Background

In 1964, Chapel Hill was a small quiet college town in the South in the midst of the civil rights movement. In the 1960 US Census, the population was 12,573 people. The local black high school was Lincoln High School on Merritt Mill Road, while the local white high school was the old Chapel Hill High School. Chapel Hill had a reputation for being a liberal college town, even back then, but in 1964 a quarter of the restaurants and motels around the town were still segregated, refusing service to African-Americans. In 1963, a sit-in campaign was organized to try to convince local businesses to integrate, and to persuade the Chapel Hill Board of Aldermen (now known as the Town Council) to pass a Public Accommodations Ordinance requiring businesses to integrate.

Watts Restaurant and Motel was a white-only hotel and restaurant on 15-501, outside of the Chapel Hill town limits at the time. The restaurant had been rebranded as Watts Restaurant from Watts Grill in 1957 by husband and wife Austin and Jeppie Watts, but the restaurant was still known colloquially as Watts Grill. During the 1950s and early 1960s, the restaurant was a popular choice to host dinner banquets for fraternities and clubs at UNC. On the first weekend of January 1964, the restaurant was chosen by protestors to be the site of several sit-ins.

Copyright held by Jim Wallace. Used under a Creative Commons license with permission from The Rock Wall where the collection resides.

The Sit-ins

On Thursday January 2, 1964, a group of student demonstrators entered Watts Restaurant aiming to be served. They included Lou Calhoun and Van Cornelius, two white UNC students, and black high school students from Lincoln High, Stella Farrar, Carolyn Edwards, and Mae Black, as well as James Foushee and Jerdene Alston from North Carolina Central University. When the demonstrators were refused service, they lay down on the floor, a common protest technique. At this point, Jeppie Watts hiked up her skirt and urinated on Lou Calhoun and James Foushee.

Lou Calhoun recalled that “I felt this stream coming down on me, and I thought ‘God, she’s got ammonia.’ I was holding my breath, trying to keep from breathing, and then she stopped, laughed and said, ‘Anybody that’d let somebody piss on them.’” Professor Al Amon from UNC, who accompanied them as a photographer, was spit upon by Mrs. Watts. Police were called, and the demonstrators were arrested for trespassing.

James Foushee was a veteran of numerous marches and sit-ins at Chapel Hill restaurants and businesses working with John Dunne, and Quinton Baker to organize them. He was arrested many times and participated in an eight-day hunger strike in 1963 in front of the Post Office as a way to change the minds of the merchants.

Jerdene Alston became a change-maker in the local civil rights movement when she was just a teenager. She recalls getting involved after seeing a flyer at her church advertising a meeting to train for the movement. As a freshman at North Carolina Central University, Ms. Alston began participating in non-violent demonstrations and sit-ins at segregated local establishments.

Copyright held by Jim Wallace. Used under a Creative Commons license with permission from The Rock Wall where the collection resides.

The following day, Friday January 3, 1964, a group of eleven, mainly professors from UNC and Duke, attempted a sit-in by going to Watts Restaurant. There were five Duke professors, Peter Klopfer (Biology), David Smith (Mathematics), Frederich Herzog (Religion), Robert Osborn (Religion), and Harmon Smith (Religion), and two from UNC, Bill Wynn and Albert Amon (both Psychology).

Alongside them were several UNC students, including Morehead scholar John Dunne, Tom Bynum, and Ben Spaulding. The final member of the group was Quinton Baker, president of the NAACP Youth Council, who was assisting the sit-in movement in Chapel Hill. The group didn’t even make it into the front door of Watts, as they were intercepted in the parking lot by the staff.

However, Professor Albert Amon, was identified from the previous evening, pulled in, and suffered severe physical abuse from Mr. Watts. During that time, the group outside was beaten and hosed down with water. While the peaceful group was being attacked both inside and outside of the restaurant, the police were summoned. Instead of being protected, the protesters were arrested and charged with a crime, while the violent attackers were not charged.

UNC student John Dunne stated, “I was brought up in a family which stressed Christian brotherhood, that emphasized that you treat everyone equally, that you don’t pick on the underdog… If one believes something, he should act according to it.”. When John Dunne came to Watts Restaurant along with Quinton Baker and others, he was not new to the risks and dangers of anti-segregation protests as he had been part of others. When Dr. Amon was pulled into the restaurant by Mr. Watts and assaulted, John ran inside and covered Dr. Amon’s prone body with his own.

Quinton Baker was the leader of the local NAACP, a leader of non-violent protests, and a leader among his black and white friends. Baker was familiar with the risks of demonstrating. Before joining professors and students at Watts Restaurant, Baker had been doused and force-fed with ammonia. On January 3rd, 1964, Baker joined John Dunne at Watts Restaurant. When Dr. Amon fell to the floor, Baker rushed inside to join Dunne to shield him from the attack.

Dr. Robert Osborn was one of the professors who walked into the Watts Restaurant that evening. As a minister in the Methodist church, Dr. Osborn strongly opposed segregation, so when invited by a former student to a nonviolent demonstration, he accepted. As the group neared the building, the doors shut. To quote from Dr. Osborn’s perspective, “I can remember very vividly the back of my shirt being pulled from my neck so the hose nozzle could be tucked under. There was, I believe, Mrs. Watts with a broom, systematically beating, hitting members of the group.”

Prof. David Smith was a Duke Professor of Mathematics. Like the others, he was there to participate in the anti-segregation protests. He too was unjustly charged with trespass. When asked by the judge if he had anything to say before the sentencing, Dr. Smith replied, “I do not believe that I have the disrespect for the law and order that is implied.”

Prof. William Wynn was a UNC Professor of Psychology and like so many others, he was criticized for his beliefs. He was physically and verbally abused, then arrested. However, even after suffering at Watts Restaurant, Dr. Wynn would not change his resolve. Dr. Wynn was given a lecture by the judge and sentenced to 90-days of hard labor.

Prof. Harmon Smith was a professor of Moral Theology. After Prof. Amon was forcefully pulled into the restaurant and beaten, the rest were unable to enter. During that time, Smith and so many others were both physically and verbally abused, then arrested. Dr. Smith was convicted of trespassing and resisting arrest, then sentenced to 90 days of hard labor. When the judge pointed out that just the day before, students had protested, and things still had not changed at Watts, Dr. Smith replied, “They were students, we were college professors; I thought we could make a difference.”

Prof. Albert Amon, the UNC Psychology professor who was brutally beaten by Austin Watts and kicked in the head, attended a number of the Chapel Hill sit-in demonstrations and took his camera to capture what happened in photos. He died in the summer of 1964 from a brain hemorrhage, possibly related to his beating at Watts Grill.

On Sunday, January 5th, a third group, including two Duke students along with Jerdene Alston and James Foushee, attempted another sit-in at Watts. On this occasion the staff poured ice water on them outside in the freezing cold and called the police who upon arrival arrested them and carried them away to jail.

The trials of the demonstrators for this and the other sit-ins took up most of the spring. Those considered to be the ringleaders of the demonstrators, Baker, Dunne, and most of the professors were found guilty of criminal trespass and sentenced to spend several months in jail or hard labor. Terry Sanford, the governor of NC, commuted the sentences of the demonstrators in December 1965, but not before they spent several months in prison or working hard labor.

One exception was Prof. Peter Klopfer, a Professor of Biology at Duke University. Like so many others that day, Dr. Klopfer refused to leave the grounds of the segregated restaurant, was arrested and charged with trespassing, even though he had not physically entered inside. When brought to court, his trial ended in a mistrial. The state declined to hold another trial leaving Klopfer in limbo, but Klopfer sued to invoke his right to a speedy trial. His case went to the Supreme Court, which ruled in Klopfer’s favor in 1967. At that point the state declined to prosecute him.

Aims of the Movement

The goal of the demonstrations was to get a Public Accommodations Ordinance passed by the board of Aldermen to require all businesses to integrate in Chapel Hill. In the words of Quinton Baker “One of the reasons that Chapel Hill became a focal point in the civil rights movement, was because it was clear that for a southern community, it had voluntarily desegregated all it was going to do…. We needed to point out that Chapel Hill was never going to voluntarily desegregate, which is what everybody was calling for at the time. Voluntary desegregation of the South, and we were saying, ‘It ain't gonna happen.’ And the way to demonstrate that was to target Chapel Hill, to make it a focal point of activity,” Proving Baker’s point, when the Chapel Hill Board of Aldermen met in 1964, they opted not to pass the ordinance. Instead integration was forced by federal legislation, the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

When the Civil Rights Act was passed, several groups went out to restaurants to test the new law. A group of six, including both whites and blacks, traveled to Watts Grill on Friday, July 3rd, 1964, where they were once again refused service and attacked. Austin Watts reportedly told them that “if they were going to be served at his restaurant, President Johnson would have to make him do it.” However, this time, Austin Watts was the one arrested and charged with assault, and another group of testers was served at Watts Grill the next day, July 4, 1964, so finally the restaurant was integrated.

Why This Matters

The sit-ins at Watts Grill were part of a broader movement in Chapel Hill that included significant protests led by black high school students as well as organizing through the black churches. The individual demonstrations at Watts Grill, particularly the story of Jeppie Watts urinating on protesters, generated outrage when reported across North Carolina. Ultimately the civil rights movement in Chapel Hill achieved its goals with the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, but at a high cost to the demonstrators.

Many Chapel Hill demonstrators faced jail time, refusing to pay fines to evade them. The student leaders of the movement spent so much time at court for trials ending in jail they were forced to drop out of school. While most were able to restart their education, some at schools in northern states, their punishment for protesting delayed their careers.

The white professors faced repercussions in their academic careers and for their families, who were often taunted and ostracized. The Daily Tar Heel summed up the contributions of the protesting professors:

“In the years to come, when all of this is behind us, UNC instructors William Wynn and Albert Amon, and Duke instructors Frederick Herzog, Robert Osborn, David Smith, Peter Klopfer and Harmon Smith, will be seen in their true light: Men who braved the winds of near universal disapproval to be true to the ideals of their God and their country, and in so doing, helped the rest of us to ultimately do likewise.” (The Daily Tar Heel, Saturday, March 21, 1964)

For more information on the sit-ins movement in Chapel Hill in the 1960s, the following books cover the period:

27 Views of Chapel Hill: A Southern University Town in Prose & Poetry Paperback, Daniel Wallace, Eno Publishers, 2011.

Game Changers: Dean Smith, Charlie Scott, and the Era That Transformed a Southern College Town, Art Chansky, University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

The Free Men, John Ehle, first published by Harper Row in 1965; reprinted in 2007 by Press 53.

Historical Essay for NCCRT Marker at Watts Restaurant, Chapel Hill, NC